This research has been sponsored by LBRY, a free, open, and community-run digital marketplace.

Designing ASIC resistant proof-of-work blockchains, and particularly hard-forking to achieve such ASIC-resistance is a contentious new issue in the cryptocurrency space. ASIC chips are custom manufactured computing devices designed specifically for a particular blockchain or hashing algorithm. As such, they are far more efficient at mining than commodity hardware such as CPUs or GPUs.

Forking to prevent such resistance, referred to as an AAHF (Anti-ASIC Hard Fork) for the rest of this article, changes the mining algorithm on a blockchain so that ASICs tailored to the old algorithm can no longer mine effectively. AAHF aren’t just theory. Recently Monero executed one and Zcash is pondering whether to do the same. At LBRY, we’ve received requests to hard fork due to the release of a Baikal miner appearing on the market (the miner is likely a FPGA machine, not an ASIC, however).

This article is a case study on the recent Monero AAHF. The Monero hard fork that occurred on April 6th was interesting in that it:

A) Set the Monero dev/community against the much maligned ASIC manufacturer Bitmain

B) Resulted in the chain splintering into various alternative projects that took over the old pre-fork chain (you can read about this here)

The goals of this article is to look at verifiable data instead of speculating about the nature of the fork, and to see what kind of lessons we can learn from it.

Effects on Hashrate

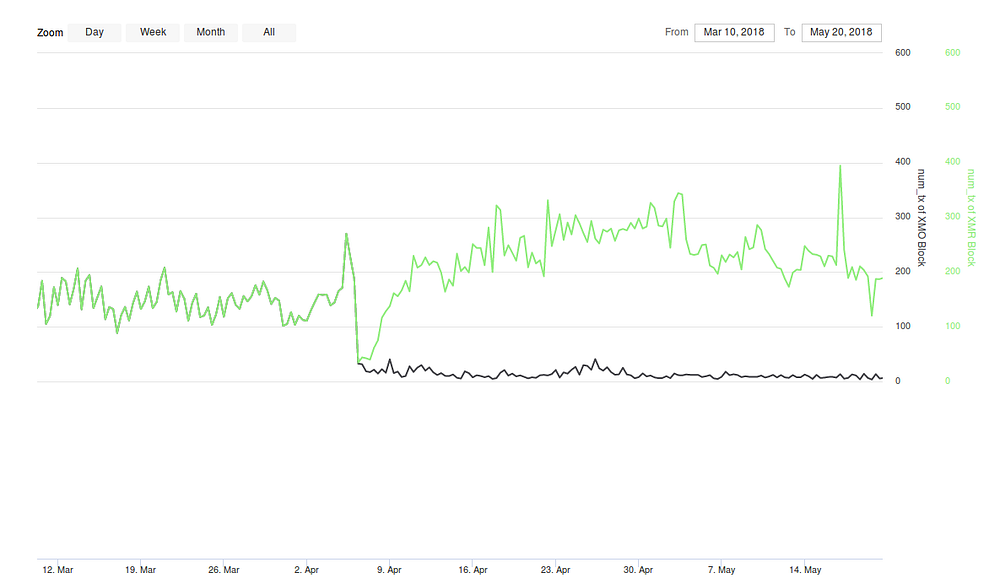

First let’s look at Monero’s hash rate before and after the hard fork. In the below graph, you can see the hashrate for Monero in green. The black line is the hashrate for the the various alt-coin splinter projects that took over Monero’s old chain after the hard fork (from henceforth called Monero Original)*.

*Note that according to GPU miners that I’ve talked to, the pre-fork and post-fork Monero POW algorithm is equivalent in computational difficulty thus the hash rate before and after the fork should be comparable.

Green: Monero hash rate, Black: Monero Original hash rate

Source: Blkdat.com

One possible interpretation of this graph is that the total Bitmain ASIC hashrate is around 500 Megahash/sec. This matches up with the amount that seemed to drop off from Monero post-fork, and also matches up with the amount that remained on the Monero Original chain post-fork. However, we can’t say this with certainty that the above interpretation is correct since it is impossible to associate hashrate to a specific type of miner.

Regardless of what the total hashrate of Bitmain’s ASIC miners is, losing almost 50% of the hashrate post fork should be a concern for Monero. The recent 51% attack of Bitcoin Gold illustrates the very real connection that exists between hash rate and security.

ASIC Capabilities

The primary argument for an AAHF is that ASIC manufacturing results in more mining centralization by pushing out the commodity hardware miners. To verify this claim, we need to look at the capability of these ASIC miners and compare them to commodity hardware. Below are the respective specs for the Bitmain Monero miner and a top of the line AMD GPU miner:

- Bitmain X3: 220 KH/s, 550 Watts, 0.4KH/s per Watt, Retail value: 1900$

- AMD HD 7990: 1.1 KH/s, 110 Watts, 0.01 KH/s per Watt, Retail value: 900$

We see that the Bitmain miner is 220 times more powerful than a single top of the line AMD GPU unit. More importantly, it is 40 times more energy efficient at mining. It is clear that commodity GPUs are outclassed by these custom miners, but it’s also important to note that there are a whole lot of GPUs out there in the world. Consider that AMD shipped 19.6 million discrete GPUs in 2017 alone. AMD does not release sale numbers for specific models, but if we assume that all 19.6 million of the GPUs sold were of the cheap 400 series variety, this adds up to 7.84 GH/s (a 400 series runs about 0.4 KH/s on the Monero network). This is 15 times larger than the 0.5 GH/s that we estimated to be the Bitmain ASICs total hashrate and the current Monero hashrate.

The point of this calculation is to show that while AMD/NVIDIA may not produce profitable miners, the total hash rate they produce is immense. ASIC producers like Bitmain may be able to obtain monopolies on profitable mining, but they have not monopolized mining. If Bitmain tries to perform a 51% attack, the Monero community will likely be able to fight it off using commodity GPUs. If we assume that 0.5 GH/s is the correct estimate for the Bitmain ASICs total hash rate, this will require 1.25 million AMD 400 series GPUs. Assuming 150 watts of power consumption per unit and 12 cents per kilowatt-hour we get the energy costs to be 22,500$ per hour. The numbers will obviously be better if we use a higher end GPU.

Aftermath for Users

Software upgrades by nature are attack vectors. Some users will end up downloading a compromised version of the upgrade which may for example send all their coins to a hacker’s address. We can actually get download numbers for Monero 0 and Monero Original. They are two projects that took over the old chain after the Monero fork and released their binaries on GitHub (GitHub tracks download numbers through their API).

About 1000 users total have downloaded either Monero Original or Monero 0 binaries and have presumably used them. I’m not suggesting that these binaries are malware but they are unsigned binaries from anonymous developers. Needless to say, there are significant risks involved in running such software. It is worth considering whether it is worth exposing users to such attack vectors when hard forking.

Other users may not even be aware that the Monero network has hard forked and may be transacting on the old network unaware of what is happening. It is impossible to tell whether the transactions happening on the Monero Original chain are intentional or accidental but the below graph shows that there is still small amount of transactions occurring on the Monero Original chain (note that the Monero Original chain is traded on hitbtc.com so the transactions below could all be intentional).

Green: number of transactions on Monero, Black: number of transactions on Monero Original

Source: Blkdat.com

Conclusions

There are several causes for concern regarding Monero’s AAHF.

The first concern is that the AAHF may have been unnecessary in the first place because the Monero community underestimated the total amount of hash rate that can be produced through commodity hardware. If the community had concerns about Bitmain abusing their powers, they certainly could have fought back without resorting to a hard fork.

The second concern is that the AAHF created attack vectors that could be exploited against its users. The lowered hash rate can be used to 51% attack the chain, and the software update necessary for the hard fork may have left users on the wrong chain or exposed them to malware.

It remains to be seen how these concerns will work out for Monero in the future. So far, things has gone smoothly as the Monero price has been stable and there has been no noticeable network disruption for the user. The market for the most part has deemed this AAHF to be a success. However, this AAHF is likely just the opening battle in a war to determine who gets to control the Monero network. Bitmain, and other ASIC manufacturer, will not be undeterred if there is money to be made. The next time this battle is fought, these concerns are going to be revisited again.